chapter_2.md 28 KB

Chapter 2 - Entities and Components

About this tutorial

This tutorial is free and open source, and all code uses the MIT license - so you are free to do with it as you like. My hope is that you will enjoy the tutorial, and make great games!

If you enjoy this and would like me to keep writing, please consider supporting my Patreon.

This chapter will introduce the entire of an Entity Component System (ECS), which will form the backbone of the rest of this tutorial. Rust has a very good ECS, called Specs - and this tutorial will show you how to use it, and try to demonstrate some of the early benefits of using it.

About Entities and Components

If you've worked on games before, you may well be used to an object oriented design (this is very common, even in the original Python libtcod tutorial that inspired this one). There's nothing really wrong with an object-oriented (OOP) design - but game developers have moved away from it, mostly because it can become quite confusing when you start to expand your game beyond your original design ideas.

You've probably seen a "class hierarchy" such as this simplified one:

BaseEntity

Monster

MeleeMob

OrcWarrior

ArcherMob

OrcArcher

You'd probably have something more complicated than that, but it works as an illustration. BaseEntity would contain code/data required to appear on the map as an entity, Monster indicates that it's a bad guy, MeleeMob would hold the logic for finding melee targets, closing in, and killing them. Likewise, ArcherMob would try to maintain the optimal range and use their ranged weapon to fire from a safe distance. The problem with a taxonomy like this is that it can be restrictive, and before you know it - you are starting to write separate classes for more complicated combinations. For example, what if we come up with an orc that can do both melee and archery - and may become friendly if you've completed the Friends With The Greenskins quest? You might well end up combining logic from all of them into one special case class. It works - and plenty of games have published doing just that - but what if there were an easier way?

Entity Component based design tries to eliminate the hierarchy, and instead implement a set of "components" that describe what you want. An "entity" is a thing - anything, really. An orc, a wolf, a potion, an Ethereal hard-drive formatting ghost - whatever you want. It's also really simple: little more than an identification number. The magic comes from entities being able to have as many components as you want to add. Components are just data, grouped by whatever properties you want to give an entity.

For example, you could build the same set of mobs with components for: Position, Renderable, Hostile, MeleeAI, RangedAI, and some sort of CombatStats component (to tell you about their weaponry, hit points, etc.). An Orc Warrior would need a position so you know where they are, a renderable so you know how to draw them. It's Hostile, so you mark it as such. Give it a MeleeAI and a set of game stats, and you have everything you need to make it approach the player and try to hit them. An Archer might be the same thing, but replacing MeleeAI with RangedAI. A hybrid could keep all the components, but either have both AIs or an additional one if you want custom behavior. If your orc becomes friendly, you could remove the Hostile component - and add a Friendly one.

In other words: components are just like your inheritance tree, but instead of inheriting traits you compose them by adding components until it does what you want. This is often called "composition".

The "S" in ECS stands for "Systems". A System is a piece of code that gathers data from the entity/components list and does something with it. It's actually quite similar to an inheritance model, but in some ways it's "backwards". For example, drawing in an OOP system is often: For each BaseEntity, call that entities Draw command. In an ECS system, it would be Get all entities with a position and a renderable component, and use that data to draw them.

For small games, an ECS often feels like it's adding a bit of extra typing to your code. It is. You take the additional work up front, to make life easier later.

That's a lot to digest, so we'll look at a simple example of how an ECS can make your life a bit easier.

Including Specs in the project

To start, we want to tell Cargo that we're going to use Specs. Open your Cargo.toml file, and change the dependencies section to look like this:

[dependencies]

rltk = { git = "https://github.com/thebracket/rltk_rs" }

specs = "0.15.0"

specs-derive = "0.4.0"

This is pretty straight-forward: we're telling Rust that we still want to use RLTK, and we're also asking for specs (the version number is current at the time of writing; you can check for new ones by typing cargo search specs). We're also adding specs-derive - which provides some helper code to reduce the amount of boilerplate typing you have to do.

At the top of main.rs we add a few lines of code:

extern crate rltk;

use rltk::{Console, GameState, Rltk, RGB, VirtualKeyCode};

extern crate specs;

use specs::prelude::*;

#[macro_use]

extern crate specs_derive;

extern crate tells Rust that we're using code from another package (or "crate"). So the first line says "please refer to rltk for this code". The use rltk:: is a short-hand; you can type rltk::Console every time you want a console; this tells Rust that we'd like to just type Console instead. The next line says "we'll be using code from specs", and the use specs::prelude::* line is there so we aren't continually typing specs::prelude::World when we just want World.

The command #[macro_use] is a little scarier looking; it just means "the next crate will contain macro code, please use it". This exists to avoid the C++ problem of #define commands leaking everywhere and confusing you. Rust is all about being explicit, to avoid confusing yourself later!

Finally, we call extern crate specs_derive. This crate contains a bunch of helpers to reduce the amount of typing you need. You'll see its benefits shortly.

Defining a position component

We're going to build a little demo that uses an ECS to put characters on the screen and move them around. A basic part of this is to define a position - so that entities know where they are. We'll keep it simple: positions are just an X and Y coordinate on the screen.

So, we define a struct (these are like structs in C, records in Pascal, etc. - a group of data stored together):

struct Position {

x: i32,

y: i32,

}

Very simple! A Position component has an x and y coordinate, as 32-bit integers. At this point, you could use Positions, but there's very little to help you store them or assign them to anyone - so we need to tell Specs that this is a component. Specs provides a lot of options for this, but we want to keep it simple. The long-form (no specs-derive help) would look like this:

struct Position {

x: i32,

y: i32,

}

impl Component for Position {

type Storage = VecStorage<Self>;

}

You will probably have a lot of components by the time your game is done - so that's a lot of typing. Not only that, but it's lots of typing the same thing over and over - with the potential to get confusing. Fortunately, specs-derive provides an easier way. You can replace the previous code with:

#[derive(Component)]

struct Pos {

x: i32,

y: i32,

}

What does this do? #[derive(x)] is a macro that says "from my basic data, please derive the boilerplate needed for x"; in this case, the x is a Component. The macro generates the additional code for you, so you don't have to type it in for every component. It makes it nice and easy to use components!

Defining a renderable component

A second part of putting a character on the screen is what character should we draw, and in what color? To handle this, we'll create a second component - Renderable. It will contain a foreground, background, and glyph (such as @) to render. So we'll create a second component structure:

#[derive(Component)]

struct Renderable {

glyph: u8,

fg: RGB,

bg: RGB,

}

RGB comes from RLTK, and represents a color. That's why we have the use rltk::{... RGB} statement - otherwise, we'd be typing rltk::RGB every time there - saving keystrokes.

Worlds and Registration

So now we have two component types, but that's not very useful without somewhere to put them! Specs requires that you register your components at start-up. What do you register it with? A World!

A World is an ECS. You can have more than one if you want, but we won't go there yet. We'll extend our State structure to have a place to store the world:

struct State {

ecs: World

}

And now in main, when we create the world - we'll put an ECS into it:

let mut gs = State {

ecs: World::new()

};

The next thing to do is to tell the ECS about the components we have created. We do this right after we create the world:

gs.ecs.register::<Position>();

gs.ecs.register::<Renderable>();

What this does is it tells our World to take a look at the types we are giving it, and do some internal magic to create storage systems for each of them. Specs has made this easy; so long as it implements Component, you can put anything you like in as a component!

Creating entities

Now we've got a World that knows how to store Position and Renderable components. So the next logical thing to do is actually make something we can draw. We can create an entity with both a Renderable and a Position component like this:

gs.ecs

.create_entity()

.with(Position { x: 40, y: 25 })

.with(Renderable {

glyph: rltk::to_cp437('@'),

fg: RGB::named(rltk::YELLOW),

bg: RGB::named(rltk::BLACK),

})

.build();

What this does, is it tells our World (ecs in gs - our game state) that we'd like a new entity. That entity should have a position (we've picked the middle of the console), and we'd like it to be renderable with an @ symbol in yellow on black. That's very simple; we aren't even storing the entity (we could if we wanted to) - we're just telling the world that it's there!

You could easily add a bunch more entities, if you want. Lets do just that:

for i in 0..10 {

gs.ecs

.create_entity()

.with(Position { x: i * 7, y: 20 })

.with(Renderable {

glyph: rltk::to_cp437('☺'),

fg: RGB::named(rltk::RED),

bg: RGB::named(rltk::BLACK),

})

.build();

}

You'll notice that we're putting them at different positions (every 7 characters, 10 times), and we've changed the @ to an ☺ - a smiley face (to_cp437 is a helper RLTK provides to let you type/paste Unicode and get the equivalent member of the old DOS/CP437 character set. You could replace the to_cp437('☺') with a 1 for the same thing). You can find the glyphs available here.

Iterating entities - a generic render system

So we now have 11 entities, with differing render characteristics and positions. It would be a great idea to do something with that data! In our tick function, we replace the call to draw "Hello Rust" with the following:

let positions = self.ecs.read_storage::<Position>();

let renderables = self.ecs.read_storage::<Renderable>();

for (pos, render) in (&positions, &renderables).join() {

ctx.set(pos.x, pos.y, render.fg, render.bg, render.glyph);

}

What does this do? let positions = self.ecs.read_storage::<Position>(); asks the ECS for read access to the container it is using to store Position components. Likewise, we ask for read access to the Renderable storage. It only makes sense to draw a character if it has both of these - you need a Position to know where to draw, and Renderable to know what to draw! Fortunately, Specs has our back:

for (pos, render) in (&positions, &renderables).join() {

This line says join positions and renderables; like a database join, it only returns entities that have both. It then uses Rust's "destructuring" to place each result (one result per entity that has both components). So for each iteration of the for loop - you get both components belonging to the same entity. That's enough to draw it!

ctx.set(pos.x, pos.y, render.fg, render.bg, render.glyph);

ctx is the instance of RLTK passed to us when tick runs. It offers a function called set, that sets a single terminal character to the glyph/colors of your choice. So we pass it the data from pos (the Position component for that entity), and the colors/glyph from render (the Renderable component for that entity).

With that in place, any entity that has both a Position and a Renderable will be rendered to the screen! You could add as many as you like, and they will render. Remove one component or the other, and they won't be rendered (for example, if an item is picked up you might remove its Position component - and add another indicating that it's in your backpack; more on that in later tutorials)

Rendering - complete code

If you've typed all of that in correctly, your main.rs now looks like this:

extern crate rltk;

use rltk::{Console, GameState, Rltk, RGB};

extern crate specs;

use specs::prelude::*;

#[macro_use]

extern crate specs_derive;

#[derive(Component)]

struct Position {

x: i32,

y: i32,

}

#[derive(Component)]

struct Renderable {

glyph: u8,

fg: RGB,

bg: RGB,

}

struct State {

ecs: World

}

impl GameState for State {

fn tick(&mut self, ctx : &mut Rltk) {

ctx.cls();

let positions = self.ecs.read_storage::<Position>();

let renderables = self.ecs.read_storage::<Renderable>();

for (pos, render) in (&positions, &renderables).join() {

ctx.set(pos.x, pos.y, render.fg, render.bg, render.glyph);

}

}

}

fn main() {

let context = Rltk::init_simple8x8(80, 50, "Hello Rust World", "../resources");

let mut gs = State {

ecs: World::new()

};

gs.ecs.register::<Position>();

gs.ecs.register::<Renderable>();

gs.ecs

.create_entity()

.with(Position { x: 40, y: 25 })

.with(Renderable {

glyph: rltk::to_cp437('@'),

fg: RGB::named(rltk::YELLOW),

bg: RGB::named(rltk::BLACK),

})

.build();

for i in 0..10 {

gs.ecs

.create_entity()

.with(Position { x: i * 7, y: 20 })

.with(Renderable {

glyph: rltk::to_cp437('☺'),

fg: RGB::named(rltk::RED),

bg: RGB::named(rltk::BLACK),

})

.build();

}

rltk::main_loop(context, gs);

}

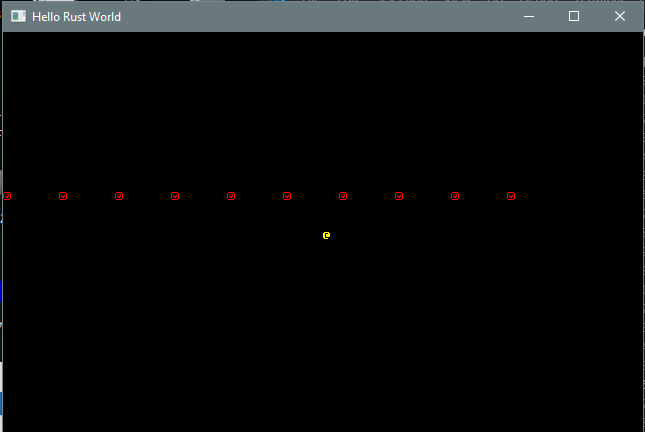

Running it (with cargo run) will give you the following:

An example system - random movement

This example showed you how an ECS can get a disparate bag of entities to render. Go ahead and play around with the entity creation - you can do a lot with this! Unfortunately, it's pretty boring - nothing is moving! Lets rectify that a bit, and make a shooting gallery type look.

First, we'll create a new component called LeftMover. Entities that have this component are indicating that they really like going to the left. The component definition is very simple; a component with no data like this is called a "tag component". We'll put it up with our other component definitions:

#[derive(Component)]

struct LeftMover {}

Now we have to tell the ECS to use the type. With our other register calls, we add:

gs.ecs.register::<LeftMover>();

Now, lets only make the red smiley faces left movers. So their definition grows to:

for i in 0..10 {

gs.ecs

.create_entity()

.with(Position { x: i * 7, y: 20 })

.with(Renderable {

glyph: rltk::to_cp437('☺'),

fg: RGB::named(rltk::RED),

bg: RGB::named(rltk::BLACK),

})

.with(LeftMover{})

.build();

}

Notice how we've added one line: .with(LeftMover{}) - that's all it takes to add one more component to these entities (and not the yellow @).

Now to actually make them move. We're going to define our first system. Systems are a way to contain entity/component logic together, and have them run independently. There's lots of complex flexibility available, but we're going to keep it simple. Here's everything required for our LeftWalker system:

struct LeftWalker {}

impl<'a> System<'a> for LeftWalker {

type SystemData = (ReadStorage<'a, LeftMover>,

WriteStorage<'a, Position>);

fn run(&mut self, (lefty, mut pos) : Self::SystemData) {

for (_lefty,pos) in (&lefty, &mut pos).join() {

pos.x -= 1;

if pos.x < 0 { pos.x = 79; }

}

}

}

This isn't as nice/simple as I'd like, but it does make sense when you understand it. Lets go through it a piece at a time:

struct LeftWalker {}just defines an empty structure - somewhere to attach the logic!impl<'a> System<'a> for LeftWalkermeans we are implementing Specs'Systemtrait for ourLeftWalkerstructure. The'aare lifetime specifiers: the system is saying that the components it uses must exist long enough for the system to run. For now, it's not worth worrying too much about it.type SystemDatais defining a type to tell Specs what the system requires. In this case, read access toLeftMovercomponents, and write access (since it updates them) toPositioncomponents. You can mix and match whatever you need in here, as we'll see in later chapters.fn runis the actual trait implementation, required by theimpl System. It takes itself, and theSystemDatawe defined.- The for loop is system shorthand for the same iteration we did in the rendering system: it will run once for each entity that has both a

LeftMoverand aPosition. Note that we're putting an underscore before theLeftMovervariable name: we never actually use it, we just require that the entity has one. The underscore tells Rust "we know we aren't using it, this isn't a bug!" and stops it from warning us every time we compile. - The meat of the loop is very simple: we subtract one from the position component, and if it is less than zero we scoot back to the right of the screen.

Now that we've written our system, we need to be able to use it. Specs includes a dispatch system that is very powerful (it can run systems concurrently, handle dependencies to figure out execution order, and so on). We're not going to use the bells and whistles yet, but it would be nice to include as a foundation to build on. Dispatchers exist on a level above the World (you can specify which world they run on!), so we'll add one to our State:

struct State {

ecs: World,

systems: Dispatcher<'static, 'static>

}

There's some more lifetimes in there, which you can not worry about for now ('static is saying that the dispatcher will last as long as the program, so Rust can stop worrying about it). We also need to build the dispatcher when we put together our state in main:

let mut gs = State {

ecs: World::new(),

systems : DispatcherBuilder::new()

.with(LeftWalker{}, "left_walker", &[])

.build()

};

We've extended State to build a dispatcher, with the LeftWalker system we made earlier. Systems also get names, and the cryptic &[] will be useful later: you use it to specify which systems depend upon the results of other systems. More on that later, when we have more systems!

Finally, we actually want to run our systems. In the tick function, we add:

self.systems.dispatch(&self.ecs);

The nice thing is that this will run all systems we register into our dispatcher; so as we add more, we don't have to worry about calling them (or even calling them in the right order). You still sometimes need more access than the dispatcher has; our renderer isn't a system because it needs the Context from RLTK (we'll improve that in a future chapter).

So your code now looks like this:

extern crate rltk;

use rltk::{Console, GameState, Rltk, RGB};

extern crate specs;

use specs::prelude::*;

#[macro_use]

extern crate specs_derive;

#[derive(Component)]

struct Position {

x: i32,

y: i32,

}

#[derive(Component)]

struct Renderable {

glyph: u8,

fg: RGB,

bg: RGB,

}

#[derive(Component)]

struct LeftMover {}

struct State {

ecs: World,

systems: Dispatcher<'static, 'static>

}

impl GameState for State {

fn tick(&mut self, ctx : &mut Rltk) {

ctx.cls();

self.systems.dispatch(&self.ecs);

let positions = self.ecs.read_storage::<Position>();

let renderables = self.ecs.read_storage::<Renderable>();

for (pos, render) in (&positions, &renderables).join() {

ctx.set(pos.x, pos.y, render.fg, render.bg, render.glyph);

}

}

}

struct LeftWalker {}

impl<'a> System<'a> for LeftWalker {

type SystemData = (ReadStorage<'a, LeftMover>,

WriteStorage<'a, Position>);

fn run(&mut self, (lefty, mut pos) : Self::SystemData) {

for (_lefty,pos) in (&lefty, &mut pos).join() {

pos.x -= 1;

if pos.x < 0 { pos.x = 79; }

}

}

}

fn main() {

let context = Rltk::init_simple8x8(80, 50, "Hello Rust World", "../resources");

let mut gs = State {

ecs: World::new(),

systems : DispatcherBuilder::new()

.with(LeftWalker{}, "left_walker", &[])

.build()

};

gs.ecs.register::<Position>();

gs.ecs.register::<Renderable>();

gs.ecs.register::<LeftMover>();

gs.ecs

.create_entity()

.with(Position { x: 40, y: 25 })

.with(Renderable {

glyph: rltk::to_cp437('@'),

fg: RGB::named(rltk::YELLOW),

bg: RGB::named(rltk::BLACK),

})

.build();

for i in 0..10 {

gs.ecs

.create_entity()

.with(Position { x: i * 7, y: 20 })

.with(Renderable {

glyph: rltk::to_cp437('☺'),

fg: RGB::named(rltk::RED),

bg: RGB::named(rltk::BLACK),

})

.with(LeftMover{})

.build();

}

rltk::main_loop(context, gs);

}

If you run it (with cargo run), the red smiley faces zoom to the left, while the @ watches.

Moving the player

Finally, lets make the @ move with keyboard controls. So we know which entity is the player, we'll make a new tag component:

#[derive(Component, Debug)]

struct Player {}

We'll add it to registration:

gs.ecs.register::<Player>();

And we'll add it to the player's entity:

gs.ecs

.create_entity()

.with(Position { x: 40, y: 25 })

.with(Renderable {

glyph: rltk::to_cp437('@'),

fg: RGB::named(rltk::YELLOW),

bg: RGB::named(rltk::BLACK),

})

.with(Player{})

.build();

Now we implement a new function, try_move_player:

fn try_move_player(delta_x: i32, delta_y: i32, ecs: &mut World) {

let mut positions = ecs.write_storage::<Position>();

let mut players = ecs.write_storage::<Player>();

for (_player, pos) in (&mut players, &mut positions).join() {

pos.x += delta_x;

pos.y += delta_y;

if pos.x < 0 { pos.x = 0; }

if pos.x > 79 { pos.y = 79; }

if pos.y < 0 { pos.y = 0; }

if pos.y > 49 { pos.y = 49; }

}

}

Drawing on our previous experience, we can see that this gains write access to Player and Position. It then joins the two, ensuring that it will only work on entities that have both component types - in this case, just the player. It then adds delta_x to x and delta_y to y - and does some checks to make sure that you haven't tried to leave the screen.

We'll add a second function to read the keyboard information provided by RLTK:

fn player_input(gs: &mut State, ctx: &mut Rltk) {

// Player movement

match ctx.key {

None => {} // Nothing happened

Some(key) => match key {

VirtualKeyCode::Left => try_move_player(-1, 0, &mut gs.ecs),

VirtualKeyCode::Right => try_move_player(1, 0, &mut gs.ecs),

VirtualKeyCode::Up => try_move_player(0, -1, &mut gs.ecs),

VirtualKeyCode::Down => try_move_player(0, 1, &mut gs.ecs),

_ => {}

},

}

}

This function takes the current game state and context, looks at the key variable in the context, and calls the appropriate move command if the relevant movement key is pressed. Lastly, we add it into tick:

player_input(self, ctx);

If you run your program (with cargo run), you now have a keyboard controlled @ symbol, while the smiley faces zoom to the left!

The final code for chapter 2

The source code for this completed example may be found ready-to-run in chapter-02-helloecs. It looks like this:

extern crate rltk;

use rltk::{Console, GameState, Rltk, RGB, VirtualKeyCode};

extern crate specs;

use specs::prelude::*;

#[macro_use]

extern crate specs_derive;

#[derive(Component)]

struct Position {

x: i32,

y: i32,

}

#[derive(Component)]

struct Renderable {

glyph: u8,

fg: RGB,

bg: RGB,

}

#[derive(Component)]

struct LeftMover {}

#[derive(Component, Debug)]

struct Player {}

struct State {

ecs: World,

systems: Dispatcher<'static, 'static>

}

fn try_move_player(delta_x: i32, delta_y: i32, ecs: &mut World) {

let mut positions = ecs.write_storage::<Position>();

let mut players = ecs.write_storage::<Player>();

for (_player, pos) in (&mut players, &mut positions).join() {

pos.x += delta_x;

pos.y += delta_y;

if pos.x < 0 { pos.x = 0; }

if pos.x > 79 { pos.y = 79; }

if pos.y < 0 { pos.y = 0; }

if pos.y > 49 { pos.y = 49; }

}

}

fn player_input(gs: &mut State, ctx: &mut Rltk) {

// Player movement

match ctx.key {

None => {} // Nothing happened

Some(key) => match key {

VirtualKeyCode::Left => try_move_player(-1, 0, &mut gs.ecs),

VirtualKeyCode::Right => try_move_player(1, 0, &mut gs.ecs),

VirtualKeyCode::Up => try_move_player(0, -1, &mut gs.ecs),

VirtualKeyCode::Down => try_move_player(0, 1, &mut gs.ecs),

_ => {}

},

}

}

impl GameState for State {

fn tick(&mut self, ctx : &mut Rltk) {

ctx.cls();

player_input(self, ctx);

self.systems.dispatch(&self.ecs);

let positions = self.ecs.read_storage::<Position>();

let renderables = self.ecs.read_storage::<Renderable>();

for (pos, render) in (&positions, &renderables).join() {

ctx.set(pos.x, pos.y, render.fg, render.bg, render.glyph);

}

}

}

struct LeftWalker {}

impl<'a> System<'a> for LeftWalker {

type SystemData = (ReadStorage<'a, LeftMover>,

WriteStorage<'a, Position>);

fn run(&mut self, (lefty, mut pos) : Self::SystemData) {

for (_lefty,pos) in (&lefty, &mut pos).join() {

pos.x -= 1;

if pos.x < 0 { pos.x = 79; }

}

}

}

fn main() {

let context = Rltk::init_simple8x8(80, 50, "Hello Rust World", "../resources");

let mut gs = State {

ecs: World::new(),

systems : DispatcherBuilder::new()

.with(LeftWalker{}, "left_walker", &[])

.build()

};

gs.ecs.register::<Position>();

gs.ecs.register::<Renderable>();

gs.ecs.register::<LeftMover>();

gs.ecs.register::<Player>();

gs.ecs

.create_entity()

.with(Position { x: 40, y: 25 })

.with(Renderable {

glyph: rltk::to_cp437('@'),

fg: RGB::named(rltk::YELLOW),

bg: RGB::named(rltk::BLACK),

})

.with(Player{})

.build();

for i in 0..10 {

gs.ecs

.create_entity()

.with(Position { x: i * 7, y: 20 })

.with(Renderable {

glyph: rltk::to_cp437('☺'),

fg: RGB::named(rltk::RED),

bg: RGB::named(rltk::BLACK),

})

.with(LeftMover{})

.build();

}

rltk::main_loop(context, gs);

}

This chapter was a lot to digest, but provides a really solid base on which to build. The great part is: you've now got further than many aspiring developers! You have entities on the screen, and can move around with the keyboard.

The source code for this chapter may be found here

Copyright (C) 2019, Herbert Wolverson.